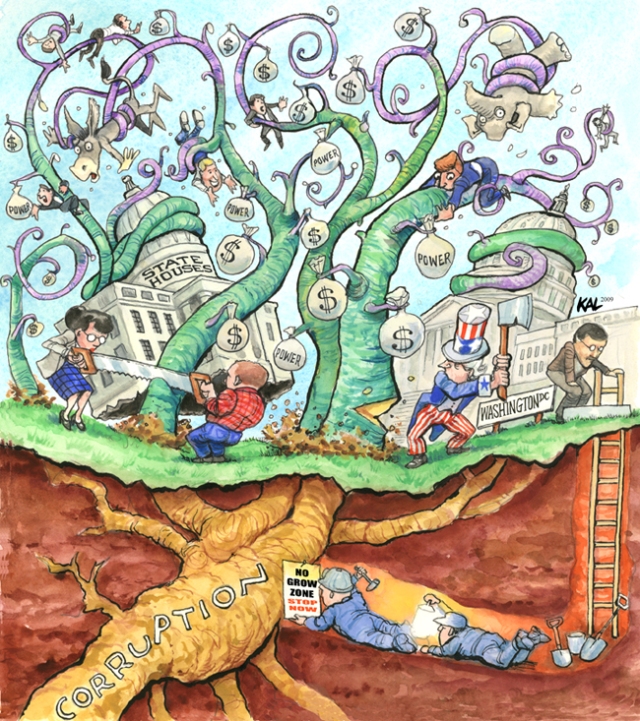

illustration by KAL (great to have met him in Sri Lanka at the US Embassy btw)

“Kabul ain’t Colombo” I said unthinkingly. My Afghan friend laughs. Leaving things in one’s car while one wanders off into a restaurant or a mall isn’t done in Kabul. Not if you want to find them still there when you come back.

Kabul isn’t Colombo by a long way. Katmandu isn’t Colombo either. For one thing we have better roads, cleaner streets and better public services. Neither is Karachi, Lahore, Delhi (our rape count is much lower for instance) or Male for that matter. For a country that likes to complain a lot, Sri Lanka has a pretty good capital city. Sure, Colombo is kind of boring and it can sometimes feel very claustrophobic and stuffy (that’s what long weekends are for) but you can still travel in public transport with relatively low risk of getting pick pocketed, same goes for the rest of the country. You don’t have that luxury say, in Europe. No Colombo and Sri Lanka are comparatively crime free.

Or perhaps I should say Sri Lanka is pretty street crime free. Most of the crime committed in Sri Lanka is carried out by the so-called civilized. The new elite and the haute bourgeoisie of post war nepotism, which is more a culture here than a contrived state of affairs. From bribery and corruption to burglary, murder and kidnappings most high profile crimes today lead upwards; into rarified stratospheres the country’s weakened law enforcement mechanisms dare not venture into.

Economically, Colombo and Sri Lanka appear to have it pretty good. We’re growing at above six percent a year, we’re doing well on indicators like global competitiveness and our human development indicators trump most of our South Asian counterparts. But Colombians and by extension Sri Lankans don’t seem to be happy. The numbers tell us that we have it good, but we’re not happy. Why?

One explanation could be that I’m an elitist. Living in a bubble of economic prosperity and social comfort that the vast majority are deprived of. Another explanation is that Sri Lankans are just a bunch of unsatisfied materialists that will stoop to anything to get at personal prosperity. And in a context of rapid development, tend to forget their own modest improvement in the face of the vast wealth accumulated by the ruling classes.

Yet another explanation is that yes, there is jealousy. But there is also strong economic discontent and dissatisfaction, exacerbated by the feeling that the top of the pyramid has it easy. The evidence is in front of us, the amount of people complaining about the rising cost of living aren’t just restricted to the poorer segments of society anymore, the number of people taking to the streets in protest of not having basic services is indicative of the failure of the state’s administrative capacities at that level.

In Sri Lanka it is normal for leaders to steal from their subjects. It is almost expected of them. The petite bourgeoisie needs role models after all. And rarely does a Sri Lankan from any walk of life think of not taking advantage of his/her position if they can. Just walk into any government public services department, have a euphemism laden conversation with a traffic policeman or see how many times that bus conductor will hand over your change voluntarily. But at the larger level, Sri Lanka’s nepotistic and hand-out based economic structure seems to be unraveling.

As an example, take the numerous accounts of foreign investors being turned away due to the myriad bribes, protection fees and other baksheesh demanded by its bureaucracy and organized crime networks, which are incidentally indistinguishable from each other. Any foreign projects approved are locked up tight with contracts awarded mainly to parasitic contractors with connections to the ruling classes. Trickle down is minimum What is worse, as the pagawa demanded rises above all reasonable levels, the amount of investment coming in is stalling, drying up reserves of cash that could otherwise have gone into appeasing the people. What trickle down there is, is stalling.

And it’s all about trickle down. Because leaders, while being allowed to enrich themselves, must also ‘take care’ of their subjects. The people must be given a part of the spoils. In effect steal from the poor and give back to the poor, but with a significant cut. The cut is forgiven if their share comes fast enough. Efficient government services thus become a hindrance to this system of patronage. But some rudimentary form of it needs to exist in order to be put into motion as and when the need to dispense some patronage comes up. It is perhaps telling that increasing breakdown of public services is happening though, that means that the upper echelons are either getting too greedy or simply running out of money.

I suspect it’s the latter. Rampant corruption has begun to deprive the economy of what efficiency it had. Political gridlocks and deep rooted biases are pitting it against an international community in a battle that threatens to permanently damage its reputation. And somewhere in the complicated system that is Sri Lanka’s political/social structure, the cogs that facilitate the smooth functioning of this hand-out machine are clogging up. Favors are not being churned out at the pace they should be. Whether there is recourse to address this problem through the coming elections is questionable. In fact, no real solutions other than the ending, or at least cutting back, of corruption can help. Aberrations, like the recent spurt of racist propaganda, have failed to distract. And people are getting angry.