ACADEMIC AND REPORT WRITING

https://independent.academia.edu/AbdulHalikAzeez

RECENT JOURNALISM AND PHOTOJOURNALISM

ACADEMIC AND REPORT WRITING

https://independent.academia.edu/AbdulHalikAzeez

RECENT JOURNALISM AND PHOTOJOURNALISM

What if I told you, that the world we live in, in something that is constructed for us, not something that is constructed by us. You and I are recipients of ideas, we are re-producers of ideas, not producers of them. Our ways of seeing the world, of perceiving it, of understanding it, and, as a consequence, of acting within it, are all determined for us, not by us.

Take for instance our idea of success. Success, after all, is the purpose of our lives. Today success is determined purely in economic terms. Whole countries are measured by financial metrics. And the general perception is that the greater our wealth, the happier we will be, and the less conflict there will be on earth. But as numerous studies have shown, this is utterly false. And the funny thing is, we know this. It is crystal clear that money doesn’t bring you happiness, we say it all the time. But today the economy isn’t working for humanity, humanity is working for economic power. But the idea of “wealth equals happiness” is so strong that it still manages to keep us working 60 hour workweeks, sometimes even more, slaving for a paradigm we don’t really believe in.

What if I told you that the biggest questions of our existence have been sabotaged by institutions. And these institutions are creating for us a version of reality that is distinctly biased in favor of those that control them. These institutions can be religious, economic, political, social or industrial. For any big idea that exists out there, there is an institution aiming to control it.

There are institutions today telling us what a government should look like, what the edicts of a given religion should be, what romantic love should look like, what beauty should look like, who a terrorist is and isn’t, what patriotism should and should not mean, which wars are just and which one’s aren’t, which causes are valid, and which ones aren’t. Even the debates we have today are mostly constructions of these self-same institutions, we are simply choosing between alternatives, not constructing our own. Freedom of thought has become an illusion.

In the true spirit of capitalism, we have outsourced even our capacity for critical thinking. Today we are told what to be and what to do in order to be happy. And it is making the world a horrible place to live in. People have become slaves to materialism, blind to murder and mass killings in their name, and are destroying the resources of the planet in the process.

And it’s a pity because a lot us, if not all of us, belong to belief systems and adhere to philosophies that tell us to question, to critique. You could be a Muslim, a Christian, a Buddhist, a Hindu, a Jew, a Socialist or a Democrat. The original purpose of every single one of your ideas was to strive to break existing molds of seeing, and give you a new set of revolutionary eyes with which to view the world.

Having been born a Muslim, I only read the Qur’an in its English translation for the first time in my life in my early twenties. It was only then that I realized how much the qur’an itself strongly calls for its readers to reflect on their surroundings, to question and to challenge existing paradigms. Vision, I realized, seeing things clearly, is central to the Islamic creed. And there is a lot in Islam today that is extremely muddied. But vision is also central to Buddhism, to Christianity, Hinduism and all other faiths and philosophies that seek to dictate how a human being should ‘be’ in the world.

If human beings cannot see clearly, we cannot function in a manner that properly takes account of the world around us. We cannot make decisions that will collectively lead to a better world. And what’s more, we collectively contribute to a world that is bad, and gets worse. Albert Einstein once said, “The world is a dangerous place not because of those who do harm, but because of those who look at it and do nothing.” Ergo, the world is a dangerous place because of you and I.

Out of this realization was born a thesis. If more people could critically connect with their beliefs, more people would see the world for what it really is. And if more people saw the world for what it is, more people would act. And if everyone acted, change will happen. As a Muslim, this becomes by purpose in life. My Jihad. Now jihad itself is a term that has been mangled by the media, and extremists alike today. This negative perception has been further bolstered by the refusal of the silent majority to stand up and contest it. Making it essentially a case study for what I am talking about.

What we see and hear of ‘Jihad’ popular discourse is picture of brutal, mindless violence. ‘Holy war’ is the most popular term used to describe it, but that’s a term that isn’t even in the Islamic vocabulary. Jihad is not ‘holy war’. In its true conception, Jihad is something we can all relate to, Muslim or no. Because Jihad simply means to strive and struggle. An internal struggle. The poet Arthur Rimbaud one said “the battle for the soul is as brutal as the battles of men”. But I would say it’s far more brutal, because the struggle here is subtle.

The Hindu philosopher Swami Chimayananda talks of an “internal guerilla warfare” because “the enemy is never out in the open, it ducks and hides, comes out and attacks and then runs and hides again”. This is what the battlefield of ideas, inside our own selves, looks like. And to paraphrase Tariq Ramadan, “If you have goal in life, then to reach that goal you have a path. And by having a path all you need to know is that you will face struggle”. Overcoming that struggle is Jihad. So Jihad may be understood through the metaphor of war, but that is about as far as it goes. And what’s more, you don’t necessarily need to be a Muslim to have a jihad.

So how do I go about my Jihad? I use whatever skills and tools I have at my disposal at the moment. And social media is one of them. The internet is another place that casts upon us the illusion of freedom, of consequence-free self-expression, and of pure unadulterated, uncensored information. And perhaps it was like that in the beginning. But no longer. Like everything else, the internet is also increasingly controlled by a few leading institutions, who now own the vast majority of the online real estate that you and I occupy. The presence of these institutions shapes what we see online, how we react to what we see, and even what we say and express. The internet influences our opinions. It mines us for commercial gain. We think we use the internet, but in reality it is mostly the converse now, the internet uses us.

But I use one of these very institutions as a platform for spreading my message. I started using Instagram in September 2012. Instagram allows you to share photographs and captions in an easy to access, easy to digest platform. Most of us tend to think that photography, while creative, cannot construct reality in the manner of a painting, which can depict anything the skill and vision of the painter can conceivably think of. But photography isn’t simply reality reproduced. A photographer has just as much leeway to manipulate reality as any artist, and he does this by manipulating what is inside the frame. Instagram adds yet another dimension that provides you with a tool to enhance your story, which is text. I do what I do by using photographic composition, and accompanying text, to ‘redefine’ the space in my own terms, to tell the story I want.

What I try to do then is to use a platform like instagram and to subvert it with my ideas. In a small way I see what I am doing as what Umberto Eco called ‘Semiological Guerilla Warfare’. According to him, reality is constructed via semiotics, signs and symbols. And the only way to challenge these signs and symbols is to attack them with your own. Mandela talked about mirroring the oppressor’s tactics as the only effective way to combat him. To me this clearly underlines what social media based activism tries to do. Instagram is my battlefield and my ‘weapons’ are my photographs and captions. And the landscape I hope to change, to shift and influence, the space I hope to ‘re-imagine’, is the landscape of ideas, of worldviews.

But change doesn’t happen easily, especially when your goal is to influence minds, and especially the minds of other people. This becomes particularly problematic when you are dealing with a platform like social media which is absolutely crowded with noise that will try to drown you out. The attention span of your target audience is less than minuscule, and the lack of sufficient metrics will tell you how many ‘likes’ you get, but won’t tell you if that ‘like’ means that someone stopped and took the time to internalize the message, or simply brushed passed with a courtesy click on the ‘heart’ button.

For internal change to happen, in my opinion and experience, there must first be a dissonance; a dissonance between the reality you see and the reality you can sense, a dissonance between what you look at, and what you see. Most of us feel this dissonance on a daily basis, but only a few of us explore it, widen it. What I seek to do then is to provide stimuli that trigger and widen this dissonance, all I can hope for really is to jolt someone just a little bit off their beaten path in the hope that one day it will help lead them in a new direction. And in the process I test my own beliefs and assumptions. And whenever I am challenged, I am forced to criticize myself. And in the process I learn. And this to me is my service to myself, to the world and to God. To connect with my beliefs and to test them, while at the same time conveying them to others. This is my Jihad.

All of us lead an existence akin to human beings in the movie, The Matrix. Or to provide a more classic example, the shackled people in Plato’s Cave. All of us are blinded by our inability to see the truth. And in that blindness are absolutely convinced that we are clear sighted. But each of us also has insights that the rest of us don’t. Each of us sense a different glitch in the matrix, and so each of us have the potential to work towards unshackling others, together to ultimately work to reveal the matrix for what it really is.

All men’s minds are a dark labyrinth. We never pause to ask if what we believe is true. But occasionally life shows us rabbit holes with fluffy white tails disappearing into enticing unknowns; or it stretches out a hand, offering us a choice between a blue pill and a red one. Take the red pill, dive into the rabbit hole. Search for your Truth. Find your Jihad. Watch out for the omens that will guide you they are literally everywhere. As the Buddha said, there are only two mistakes one can make on the road to truth, not going all the way, and not starting.

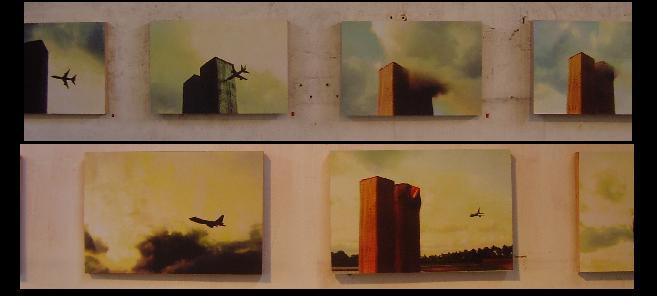

Photo of ‘World Trade Centre’ by Anuradha Henakaarachchi at the Colombo Art Biennale 2009.

Originally published in Groundviews

I was sitting in my garden, gazing at the stars listening to my Walkman, which was the only thing to do back then as you ticked off the minutes until the regulated power cuts that cursed Sri Lanka at the time wore away, every night, when I heard the absurd news. Planes hitting the twin towers and then causing them to fall down? And they say a Muslim did it, some guy in a turban and thobe with a long beard sitting in a cave in Afghanistan. I could barely place Afghanistan on a map.

Weeks became months and as more news of Bin Laden flooded the world I sunk further into my mid-teen bubble of O/Levels and school; music and movies and street cricket. This was a bubble I had always been in, but unbeknownst to me its surface had already been breached.

The breach became a gaping hole one day after an Interact Club meeting, I was walking ahead and behind me a girl, in a borrowed Fox News accent, jokingly referred to the boys she was with as ‘Funnamentahlist Muzlehms’. I had heard the term on the TV back then, but it had never struck me with so much force as it did then, overhearing it in a random conversation on a street in Maradana.

Because here was a new category of Muslim, given birth to in America and now brought to the streets of Sri Lanka. Revealed to me in its rawest form, with the original accent still coloring it; the newborn Fundamentalist Muslim. Though no one back then, and no one still, has succeeded in successfully defining what his moniker means, his invasion into my bubble began to force me to confront certain… realities.

He refused to acknowledge my own Muslimness for one. My Muslimness was a rather dormant part of my identity then, more or less a cultural marker that differentiated me from non-Muslim friends. It involved certain rituals like going to the mosque on Friday and hurriedly going through the motions of daily prayers when the inclination struck me. But this new ‘Fundamentalist Muslim’ was having none of that.

As the years passed, his voice became louder and louder. He was staring down my drab, boring Muslimness; ignoring him wouldn’t make him go away. He wanted my Muslimness to man up. “There are lines being drawn up”, he seemed to say. “Which side will you choose?” I was either with him or against him. Familiar words, back then, to those that eventually supported Bush’s War on Terror.

But I am no terrorist, I don’t believe the killing of innocent civilians is a part of Islam. So if you’re looking for an apology from me on the anniversary of 9/11, you can stop looking now. I don’t relate to the people who did the crime just because we ostensibly share the same religion. Just as much as people who believe in ‘democracy’ and ‘freedom’ don’t relate to the war crimes in their name that have shed the blood of hundreds of thousands before 9/11 and since.

On the other hand, there were the voices forcing me to become a ‘moderate Muslim’. A Muslim that unconditionally gives himself up to materialism, maybe has a drink on occasion, a Muslim that does not question extant global power structures, a Muslim that does not stand up for justice, compassion and equality; in short, a Muslim that is Muslim only In name.

But I am not a so-called ‘moderate Muslim’ either. I resent being on someone’s alien scale of what it means to be Muslim. Categorized as being somewhere in between a Muslim that drinks and smokes and a Muslim that kills innocent civilians. I reject the label ‘moderate Muslim’ just as much as I reject the label ‘Fundamentalist Muslim’ not only because they’re both meaningless essentializations, but because they place my faith within a worldview that presupposes its evidential guilt.

My identity as a Muslim, struggling with my refusal to be boxed into labels invented by Islamophobes and neo-khawarij alike, has evolved over the years in a continuing process. After more than a decade of soul searching, my Muslimness now definitely dominates my worldview. But 13 years on I still haven’t worked out what ‘kind’ of Muslim I am or must seek to be; I strongly suspect that I need not be any kind of Muslim other than simply a Muslim, inasmuch as it only means a slave that submits to God’s will and leads a life seeking only His pleasure.

9/11 wasn’t the trigger for a religious awakening. But it was one more event in my life, perhaps the first, which woke me up to realities that I was previously comfortable ignoring. It not only helped introduce the world to me it forced me to confront things like heritage and history, beliefs and ideology. It was so big that it refused to be ignored.

And I’ve learned a thing or two since then. I have learned that to look at the world in terms of generalizations such as ‘America’ and ‘Islam’ is to buy into the propaganda that perpetuates the violence of our times. The obscurantism via generalizations that the media and extremist propaganda alike feeds us conceals the real workings at play; the corrupt politics; the propped up oppressive regimes; the warmongering; the ruthless corporations; the proxy wars; and most importantly, the long arm of history.

Looking along the accusative finger pointing after 9/11, I began to also see the numerous fingers pointing back. Now I realize that this is a discourse between extremists on either side, and we’re all stuck in the middle. The mostly deluded, self-absorbed majority, the silent victims.

Originally published on Groundviews under a pseudonym.

Kiru is a soft spoken but hard-nosed activist from Jaffna. He and I both attended the opening ceremony of the recently concluded World Conference on Youth (WCY) in Hambantota, and he and I both watched as the President got up on stage and spoke about the eradication of terrorists, and of the successful re-integration of ex-combatants into society. The tone was heroic, victorious, Sri Lanka had ‘done away with terror’ and was ‘on its way’ to paraphrase Bathiya and Santhush’s lyrics for the Conference’s theme song.

Kiru had lost his mother to cancer and the LTTE when he was twelve. She couldn’t be brought into Colombo for treatment because the way was blocked. The care she needed simply wasn’t available in Jaffna at the time, and so her three boys and husband had no choice but to simply watch as she slowly succumbed. Today Kiru works with people traumatized by conflict; the post war displaced, ex-combatants, war widows, children.

Later that night, he told me how ex-combatants, former heroes in their villages, are now less than nothing. Repeatedly harassed by armed forces, they have no privacy and they are free only in name. Many of them, depressed, have resorted to suicide. Kiru’s voice shakes with emotion. The Tamil population in the North, by and large, are regarded with acute suspicion. Public gatherings are closely watched. Extra-judicial justice is doled out liberally by paramilitaries that are watching for just the hint of a step in the wrong direction.

In the beginning of this year I witnessed long-time residents of Colombo being uprooted from their ancestral homes with little more than a few weeks’ notice. The social costs of such a massive internal displacement of peoples completely ignored in the driving urge of greed and ‘economic growth’.

In 2013 I witnessed and participated in anti-hate campaigns in Sri Lanka, protesting against emerging Islamophobia and anti-Muslim sentiment. The Bodu Bala Sena and its ilk, once in possession of an almost overwhelmingly powerful voice in the country, has now seemingly lost some of its influence. But it still operates and threatens to re-emerge in force; having forged ties with the deadly 969 movement in Burma, extremists that have set in a motion a genocide against Burmese Rohingya. It is not a stretch to imagine that the Bodu Bala Sena would like to see the same thing happen to Sri Lankan Muslims.

Everywhere, I see matters dealt with hardness. With very little tact, genuine sensitivity and caring, concepts that should have been at the top of our post war agenda for the country. The Lessons Learned for Reconciliation Commission (LLRC)’s recommendations have been all but brushed under the carpet. It is as if we as a nation have simply refused to acknowledge our past. Like much of our attitudes to mental illnesses and psychological scars, we choose to gloss over, ignore, walk-over. Choosing to point at the faults of our critics instead.

I grew up in the war, not in the same way as those who were actually in the warzones, but my childhood was clouded by spells of terrified thought that I would lose one of my parents to a bomb blast. One night, when my father took hours to return home after the train bombings of ‘96, a commute he usually made after work, my fears were almost realized. Almost. One of my friends wasn’t so lucky, his father died in that train, and his mother permanently lost her sight.

Life was full of bad omens then. The plume of black smoke I saw from my 3rd floor classroom, rising into the air after a bomb blast in ’98; the plastic makeshift window-covering bursting free with a loud pop as the Central Bank bomb of ‘96 went off. Chaos at school, teachers relating stories of bloody corpses and mangled bodies to each other; heedless of listening kids. The severed head of a suicide bomber on TV became an almost routine, expected sight.

Looking back I am surprised and very thankful to the Almighty that the war never really touched me. And I am grateful, grateful more than anything else that the war has ended. We are definitely freer, more liberated and safer. I salute the government for its efforts in that. No one likes to talk about the gluttony of war until it ends. War today, it seems, is never clean. Which, I think, is why the whole human rights debate provokes so many mixed feelings among Sri Lankans.

But as long as the war didn’t directly touch me I was happy to be as ignorant of it as possible while it lasted. But I can’t afford that luxury now. Because life is again full of bad omens. As I sit here and reflect on the last five years I realize one thing, and one thing only. This realization is not some major intellectual breakthrough that will now change the direction of our post war discourse. It is a very simple realization. One that I know many others of my generation have come to. The realization is this; the war is now over, but the conflict still isn’t.

###

I know a lot of people here are idealistic, I am too. I’m just a little cynical about the mechanisms we usually use in order to get what we want. Getting what we want (‘we’ being ‘the youth’, an over-homogenized entity that sometimes does not make sense), being the primary goal here at WCY2014 and similar conferences we attend. My frustration usually stems from the fact that no one usually looks in-the-face of the most urgent problems of our time, problems from which most of the issues we want to tackle arise from the first place.

There was very little deep discourse, for instance, on the wars and oppressions raging in the world today. Where essentially respected nations within the global community are carrying out dastardly acts with grave violations of human rights. There was next to no discussion about the corporatocracy, the military industrial complex, puppet regimes, the exploitation of resources in the name of capitalism, phenomenon that are invariably nicely packaged in boxes labelled ‘democracy’, ‘progress’ and ‘freedom’ for gullible minds to consume, distorting what those original concepts should mean to us to begin with.

Take the Arab Spring, the most touted example of this century, bandied about by practically everyone trying to convert people into believing in the ‘potential of youth’. The Arab spring has completely failed in almost all the places it has ‘sprung’ up in, with Tunisia being the only possible exception. Wherever else the Arab Spring raised its head, born by the boiling frustrations of young people long oppressed by regimes backed by the global status quo, it has only been compressed again, the most blatant example of this being Egypt, where a military coup that killed nearly 700 innocents is now holding forth as the only hope for democracy in the country. A regime fast gaining support and legitimacy from around the world despite its many ongoing violations.

We talk about climate change and the carbon footprint, yet most climate problems stem from activities of large corporate entities that are simply not represented here. This literally makes it impossible to engage meaningfully with one of the main stakeholders on the issue. These same corporates, again, are supported by governments that bring legitimacy to conferences such as these, and preserved and natured in the name of capitalism and economic growth. So, I think, what kind of game are we playing here? Are conferences such as these merely put in place to pander to the enthusiasm of youth? A way of harnessing their energy? A way of diverting it away from where it would have been expended otherwise? In bloody smash-yourself-against-the-wall-revolutions born of desperate frustration perhaps?

Young people almost by definition are frustrated. I think being frustrated and concerned about problems and issues is something that ties us together as idealists, as those that are young. Because what else does? I have met many kinds of young people. Strong, weak, happy, sad, apathetic and simply downright evil. I have met young people that in my opinion should in no way be allowed anywhere near a position of power. Young people in that sense are just like old people. But young people at least, are less likely to take things lying down.

Most of the ‘old people’ that spoke to us over the last few days, like John Ashe, the president of the general assembly of the UN, indicated how the baton is now being passed, about how his generation was not as successful as he hoped it would be. How the world’s problems, decades on, are still more or less the same. This is a huge responsibility and also a burden on our shoulders. Because what guarantee do we have that our approach will yield better results? Are we, in an Einsteinian spell of madness, going to go about solving our problems in the same way as those before us, repeating their oversights and mistakes? Or are we not only going to aim for change, but also in a change in how we approach change?

From the beginning of the conference, the unofficial word on the street was that we were not to expect a revolutionary outcome document. The point is the process, changing the process here is what was important. Wangari Maathai, the famous Kenyan activist, left us with the tale of the hummingbird, who patiently travelled back and forth from the river in an attempt to douse the flames consuming her jungle home even as all other animals fled. We must all be hummingbirds for change, she said. And hummingbirds are what I see when I look at the delegates of WCY2014.

Plenty of people here believe this conference can and is contributing to change in a positive way. At least in terms of process. If this goes ahead as planned, the post-2015 development goals will essentially be influenced by actual youth input. For the first time in like, ever, young people would have actually contributed their bit into global policy formulation; having their say in how policies of countries around the world address issues such as gender, human rights, health, governance and what have you. This, even I can admit, is nothing to sneeze at.

Adams Peak can be a grueling trek but ultimately extremely rewarding. The cultural aspect especially, which makes it stand to reason to attempt it in the pilgrimage season. This was from last year. We trekked up half the distance through a jungle path* that only opens up when the villagers of Udamaliboda begin to use it for their own pilgrimage. The path is otherwise usually covered in thick undergrowth and you are likely to get lost if you attempt it at any other time. Also, even at the best of times, the risk of flash floods is real.

When you reach the steps proper, which in our case consisted of little more than rough cuts made into rock (the Kuruvita route. The more civilized paths lead up from Hatton and Ratnapura, the former is crowded and touristy, while the latter is longer but more peaceable and one with nature), and meet other pilgrims on their way up or down, they will greet you in verse invoking upon you the blessings of the god Saman, the deity of the mountain. You are generally expected to respond in kind, or bear the brunt of the uncomfortable silences that follow with respectful, sheepish smiles.

The mountain’s Sinhala name, Samanala, derives from the name of this god or also possibly the Sinhala word for butterfly, which is the same. The whole area surrounding the mountain, which is sacred and steeped in ancient lore and significance associated with all four major faiths the island hosts but primarily in the belief systems of the Sinhala people, is known as ‘the realm of the mountain god’ or ‘Samanala adaviya’, to those that revere it. It is also known as ‘Shri Pada’ (for the sacred footprint on its peak said to belong to Adam, Shiva or the Buddha based on which belief system you subscribe to) or Adam’s Peak.

There are four main paths that lead to the peak, and attribute it to what you will, but ascending or descending along the lesser populated ones, it is not hard to gather a sense of otherwordly profundity in every leaf that brushes your face, in the clumps of big rock roughly hewn to make way for human progress, in the breathtaking views and sights that greet you as you progress upwards or in every rivulet of icy water that crosses your path; from thin streams to the gushing majesty of the ‘seetha gangula’ or ‘cool river’ in which it is considered especially auspicious to bathe in.

In the case of the path we took, every leech that successfully latched on to our foot in tenacious determination, sucking our blood and giving us the itches for weeks afterwards, also succeeded in conveying something otherworldly, just not so much in a good way. But if you are up for a tough hike, I would strongly recommend the path from Udamaliboda. In an age of ease and convenience, it alone remains one of the only truly ‘authentic’ ways up there. I know, I sound like such a hipster.

Remarkable people come to the peak. I saw old men and women, some supporting themselves with walking sticks resolutely making their way upwards, even passing us, our poor touristy tread unfired by any sense of profound purpose, in an amazing testament to the power of human faith. Whole families, nay, whole villages will come up the mountain together, many will carry toddlers all the way up and all the way back down. They will bring supplies and cook and sleep and live their way up the mountain, often taking days to complete the pilgrimage, taking advantage of the many ‘ambalamas’ or resting places constructed for the purpose.

It is said that Ibn Batuta, the famous Moroccan Islamic jurist who pretty much made an envious lifelong career out of traveling and writing about it, talked the Tamil king of the North at the time into taking him to the peak. He must have gone through thick jungle, forbidding trials, and territory belonging to Sinhalese kings, but he doesn’t appear to have experienced any untoward problems. In Islamic tradition, including the prophet’s (may peace be upon him) hadeeth, there is some evidence that Adam could have alighted upon Sarandib, but there is evidence just as strong that makes the case of him having landed in Jordan. Anyhow, it appears that Muslim traders initially made a big deal of the former, which also resulted in increased access to the hinterlands, and expansion of the trade in gems, both a spiritually and commercially profitable enterprise.

The multiculturalism of Adam’s peak however, I can attest to. When I found myself up there before sunrise, I was anxious to offer my pre-dawn salah. This was at the height of BBS induced anti-Muslim hate in the country, and being the city slicker I am, I naively feared I would be mobbed in mid-prayer. The top of the mountain is a warren of construction; temples and viewing platforms; sprawling resting places, all squeezed into a very small piece of land right on the peak, which incidentally results in terrible foot traffic jams along the more crowded Hatton route, which sort of beats the purpose of taking the shorter, more commercial path to the top.

I apprehensively laid my prayer rug amidst sleeping bodies, in what I thought was a secluded corner. And proceeded to pray. I kept hearing hubbub in the background, hubbub which I expected to rise to a crescendo of outrage at any moment. But nothing happened. I prayed, nodded at a few groggy people just waking up, and left. I felt unnoticed, unremarked upon, and more than anything else that could have happened, that made me feel welcome, a part of the crowd.

Nothing really left to talk about except for the sunrise, which everyone waits for, and which is pretty much the point of the whole exercise for those that aren’t religiously motivated. There is a very long moment of staring into the East, hundreds of people literally looking towards the East, faces open and expectant as if hoping for some sort of divine revelation. And the sun is a total tease. It made us wait and wait, and finally deigned to let loose a single gleam, a ray as sharp as a laser beam piercing through the crowd, before finally rising completely to the occasion.

The sun will soon be too bright to look at, but if you glance off the Western side of the mountain, you will see the massive triangular shadow of the peak stretching to the horizon, the mist still caught in the valleys of lesser peaks look like trapped lakes. It is truly a breathtaking sight.

*information on trails and travel advice to Adam’s Peak can be found on the excellent Lakdasun

Dayan Jayatilleka spoke at a recent event organized by the Sri Lankan Committee for Solidarity with Palestine, to commemorate the UN Day for Solidarity with Palestine . The Sri Lankan government has made it a general point to sympathize with the Palestinian cause, though in recent years it has also become increasingly pally with Israel, with an envoy in the country and multiple arms deals.

DJ himself has a long and robust history of support for the Palestinian cause. But his speech on that day smacked of opportunism aimed at capitalizing on one of the world’s most tragic human rights issues in order to express the grievances of Sri Lanka’s government.

His attempts to equate the troubles of the Palestinian people with the ‘troubles of the Sri Lankan people’, whatever that may mean drastically trivialized the Palestinian problem. According to him, Sri Lanka and Palestine are two sides of the same coin, because they are both subject to double standards by ‘hegemonic Western regimes’.

I don’t quite know what Sri Lanka DJ is taking about, unless he’s talking about the extremely poor or the post-war disenfranchised, but even they don’t experience problems remotely close to what Palestinians experience everyday; sewage flooding their streets, constant threat of death by drone strikes/air strikes/deranged Israeli soldier strikes, frequent checkpoints, the inability to enjoy one’s rights in one’s own country, constant threat of expulsion and murder at the hands of an opressive regime etc etc etc. The list goes on.

To say that Sri Lanka and Palestine have something in common because we are both subject to double standards by Western regimes is like equating an advanced cancer patient with someone complaining about a visit to the dentist.

Also consider that in the eyes of the West, the government of Sri Lanka is accused of crimes that liken them more to Israel than Palestine; cast more in the mold of the oppressor than the oppressed. And all it seems to be doing is playing the part of the prosecuted street thug plaintively pointing at the gangland boss going free. This posturing is an admission of guilt, not of innocence.

DJ went on to make an explosive exhortation for David Cameron to visit Palestine, and not Jaffna, if he cares about human rights. I think David Cameron is quite aware of the tragic state of Palestine. He staunchly ignores it everyday, never meaningfully addressing the problem that the ‘Western Hegemonic Powers’ Dayan talks about created in the first place. But unlike Palestine, Sri Lanka’s problem is completely internal. We have the power to solve it, address it and move on from it. The Palestinian people do not have this luxury.

The moral agency of the West (what moral agency of the West?) is just a diversion, and it’s sad to see someone like DJ actively engaging in promoting it as the predominant point in Sri Lanka’s post war discourse, dialog and search for truths. Instead we should be looking inwards, into our own history, into our own morality. I have always been and still am staunchly against the LTTE, and I am more grateful than I can say that the war is now over, and the terrorists ‘defeated’.

But i’d be lying if I said that I believe the conflict has ended. Sri Lanka’s conflict is living on, and it is constantly being aggravated in its sleeping underground state by inaction, jingoism and distraction. And no one seems to be taking a meaningful public stand to address it. The conflict is a sleeping dragon, and eventually it is going to wake up.

illustration by KAL (great to have met him in Sri Lanka at the US Embassy btw)

“Kabul ain’t Colombo” I said unthinkingly. My Afghan friend laughs. Leaving things in one’s car while one wanders off into a restaurant or a mall isn’t done in Kabul. Not if you want to find them still there when you come back.

Kabul isn’t Colombo by a long way. Katmandu isn’t Colombo either. For one thing we have better roads, cleaner streets and better public services. Neither is Karachi, Lahore, Delhi (our rape count is much lower for instance) or Male for that matter. For a country that likes to complain a lot, Sri Lanka has a pretty good capital city. Sure, Colombo is kind of boring and it can sometimes feel very claustrophobic and stuffy (that’s what long weekends are for) but you can still travel in public transport with relatively low risk of getting pick pocketed, same goes for the rest of the country. You don’t have that luxury say, in Europe. No Colombo and Sri Lanka are comparatively crime free.

Or perhaps I should say Sri Lanka is pretty street crime free. Most of the crime committed in Sri Lanka is carried out by the so-called civilized. The new elite and the haute bourgeoisie of post war nepotism, which is more a culture here than a contrived state of affairs. From bribery and corruption to burglary, murder and kidnappings most high profile crimes today lead upwards; into rarified stratospheres the country’s weakened law enforcement mechanisms dare not venture into.

Economically, Colombo and Sri Lanka appear to have it pretty good. We’re growing at above six percent a year, we’re doing well on indicators like global competitiveness and our human development indicators trump most of our South Asian counterparts. But Colombians and by extension Sri Lankans don’t seem to be happy. The numbers tell us that we have it good, but we’re not happy. Why?

One explanation could be that I’m an elitist. Living in a bubble of economic prosperity and social comfort that the vast majority are deprived of. Another explanation is that Sri Lankans are just a bunch of unsatisfied materialists that will stoop to anything to get at personal prosperity. And in a context of rapid development, tend to forget their own modest improvement in the face of the vast wealth accumulated by the ruling classes.

Yet another explanation is that yes, there is jealousy. But there is also strong economic discontent and dissatisfaction, exacerbated by the feeling that the top of the pyramid has it easy. The evidence is in front of us, the amount of people complaining about the rising cost of living aren’t just restricted to the poorer segments of society anymore, the number of people taking to the streets in protest of not having basic services is indicative of the failure of the state’s administrative capacities at that level.

In Sri Lanka it is normal for leaders to steal from their subjects. It is almost expected of them. The petite bourgeoisie needs role models after all. And rarely does a Sri Lankan from any walk of life think of not taking advantage of his/her position if they can. Just walk into any government public services department, have a euphemism laden conversation with a traffic policeman or see how many times that bus conductor will hand over your change voluntarily. But at the larger level, Sri Lanka’s nepotistic and hand-out based economic structure seems to be unraveling.

As an example, take the numerous accounts of foreign investors being turned away due to the myriad bribes, protection fees and other baksheesh demanded by its bureaucracy and organized crime networks, which are incidentally indistinguishable from each other. Any foreign projects approved are locked up tight with contracts awarded mainly to parasitic contractors with connections to the ruling classes. Trickle down is minimum What is worse, as the pagawa demanded rises above all reasonable levels, the amount of investment coming in is stalling, drying up reserves of cash that could otherwise have gone into appeasing the people. What trickle down there is, is stalling.

And it’s all about trickle down. Because leaders, while being allowed to enrich themselves, must also ‘take care’ of their subjects. The people must be given a part of the spoils. In effect steal from the poor and give back to the poor, but with a significant cut. The cut is forgiven if their share comes fast enough. Efficient government services thus become a hindrance to this system of patronage. But some rudimentary form of it needs to exist in order to be put into motion as and when the need to dispense some patronage comes up. It is perhaps telling that increasing breakdown of public services is happening though, that means that the upper echelons are either getting too greedy or simply running out of money.

I suspect it’s the latter. Rampant corruption has begun to deprive the economy of what efficiency it had. Political gridlocks and deep rooted biases are pitting it against an international community in a battle that threatens to permanently damage its reputation. And somewhere in the complicated system that is Sri Lanka’s political/social structure, the cogs that facilitate the smooth functioning of this hand-out machine are clogging up. Favors are not being churned out at the pace they should be. Whether there is recourse to address this problem through the coming elections is questionable. In fact, no real solutions other than the ending, or at least cutting back, of corruption can help. Aberrations, like the recent spurt of racist propaganda, have failed to distract. And people are getting angry.

Town Hall/ White House

Original post from the SAES blog. I’m blogging and tweeting from the South Asian Economic Summit along with a few others, hastag #saes2013.

This morning Pakistani economist Akmal Hussein talked about how mainstream economics/capitalism teaches that inequality is essentially an un-avoidable by product of growth. He said that equity is not only a measure of social justice but can also be a powerful driver of growth. You just have to open the lower and middle classes to opportunities to grow, giving you a much bigger base.

Great sentiments, I agree 100%. But how easy is it to talk about equitable growth while many countries in South East Asia are facing a ‘neoliberalize or die’ situation? And indeed, are enthusiastically jumping in the very same capitalist bandwagon that facilitates this systematic inequality. India for example is notorious for facilitating corporate expansion. It is, in fact, one of the most characteristic features of its growth. I think the tendency is to hope that equity will come after wealth is achieved, but if the West is any example, a semblance of equity within one’s borders is only achievable by impoverishing peoples beyond it.

Earlier still Ahsal Iqbal Chowdhry, Federal Minister For Planning in Pakistan, spoke bold words about the ‘failure’ of the Washington consensus, and even mentioned discarding it for a Colombo consensus, whatever that may mean, hopefully achievable starting today. But seeing as the most powerful economy in the region got its early nineties boost by the very same Washington Consensus, has it really ‘failed’ in that sense? What would India have been if it wasn’t bailed out? If it wasn’t invested in heavily by Western corporations?

I’m not defending the Washington Consensus, far from it. It has indeed created a lot of harm by seemingly creating growth, but it is ironic that it is this very growth that we celebrate, and hope to convert into something that is fundamentally against its nature. The Washington consensus ‘worked’ because it was essentially hegemonistic. It is the patronage of the powerful to the weak, and beggars cannot choose luxuries like equity.

Will Choudhry’s imagined Colombo Consensus incorporate some similar form of hegemony? Assuming it can even shrug of its Western counterpart as easily as he makes it sound. Indeed can South Asia with all its deep running conflicts, ever form a collective without some entity dominating?

Perhaps the fear of outside interference can enlighten the region to the benefits of mutual cooperation. But it has already incorporated many elements of Chowdhry’s ‘Washington Consensus’, perhaps too many to think of turning back without completely destroying and remaking itself. Perhaps in retrospect, it is telling that both speakers were Pakistani?